Tasks such as envelope following, dynamics processing, and soft saturation often rely on low-pass filtering in which the cutoff frequency of the filter (which you can alternatively think of as its reaction speed) varies according to whether the input is rising, stable, or falling. For example, a VU meter design might call for an envelope follower whose output can rise quickly but then drops off more slowly. To make this we could use a low-pass filter to make a moving average of the instantaneous signal level, but the moving average should react faster on rising inputs than on falling ones.

The simplest type of digital low-pass filter can be understood as a moving average:

y[n] = y[n − 1] + k ⋅ (x[n] − y[n − 1])

where 0 ≤ k ≤ 1 is an averaging factor, usually much closer to zero than one. When the value of k is small enough (less than 1/2, say), it is approximately equal to the filter’s rolloff frequency in units of radians per sample. (The theory behind this is explained in Theory and Techniques of Electronic Music, section 8.3, “designing filters”).

For our purposes we’ll rewrite this equation as:

y[n] − y[n − 1] = f(x[n] − y[n − 1])

where the function f is linear:

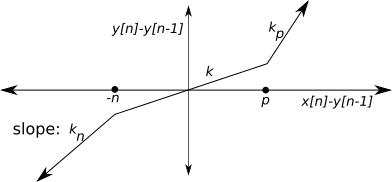

f(x) = k ⋅ x

In words, this equation says, “increment your output by k times the distance you have to travel to reach the goal x[n]”. (So far, we’ve described the action of the linear lop~ object.) In the slop~ object, this linear function is replaced by a nonlinear one with three segments, one for an interval ( − n, p) containing zero, and two others joining this one at the input values − n and p. The three segments have slopes equal to kn, k, and kp for the negative, middle, and positive regions:

Rationale. In general, k could depend on both the previous output y[n − 1] and on the current input x. This would require that the invoking patch somehow specify a function of two variables, a feat for which Pd is ill suited. In slop~ we make the simplifying assumption that adding an offset to both the filter’s state and its input should result in adding the same offset to the output; that is, the filter should be translation-invariant. (As will be seen below, through a bit of skulduggery we can still make translation-dependent effects such as soft saturation). One could also ask why we don’t allow the function f to refer to a stored array instead of restricting it to a 5-parameter family of piecewise linear functions. The reason for choosing the approach taken is that it is often desirable to modulate the parameters at audio rates, and that would be difficult if we used an array.

The following four examples are demonstrated in subpatches of the slop~ help file. (If your browser is set up to open “.pd” files using Pure Data then you can open it with this link; alternatively you can create a slop~ object in a patch and get help for it, or navigate to it using Pd’s help browser.)

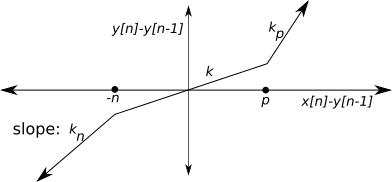

The output signal y[n] has a time-varying slope equal to (y[n] − y[n − 1])/τ, where τ denotes the elapsed time between two samples, equal to one over the sample rate R. The slope can be rewritten as R ⋅ (y[n] − y[n − 1]). Suppose we wish to create an output signal whose slope is limited between two values − sn and sp (so sn and sp, both greater than zero, are the maximum downward and upward slope). This implies that we should limit the difference between successive outputs, y[n] − y[n − 1] to lie between − sn/R and sp/R. We therefore increment the output by a quantity x[n] − y[n − 1] as long as that increment lies between those two limits. Beyond those limits the response speed should be zero so that the increment doesn’t vary past those limits. To do this we set the five filter coefficients to slop~ to k = 1, n = sn/R, p = sp/R, and kn = kp = 0. Since the three speed inputs to slop~ are in units of Hz, we can set k = 1 by giving a linear-response frequency higher than the sample rate. (In practice, “1e9”, meaning a billion, will do fine for any sample rate we expect to encounter.)

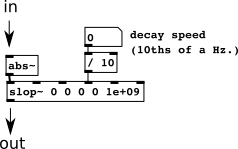

A patch to do this is shown here:

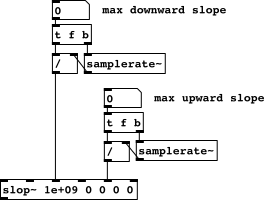

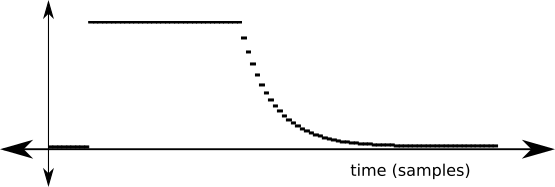

A sample input and output are shown here:

The input is a square pulse of unit height lasting 0.7 msec, at a sample rate of 48000. The upward maximum slope is set to 9000. For the first 5 samples of the pulse, the upward increment is limited to 9000/48000 units. At the sixth sample of the pulse the input is within that limit of the previous output, and so the increment becomes exactly what is needed to make the output reach the input in value.

Note: slew limiting is useful for conditioning time-varting controls to avoid discontinuities. It’s not so useful as a way to generate triangle waves from rectangular pulse trains, because the rising and falling edges are quantized to an integer sample number, making audible (and ugly) non-periodicities.

To make a peak meter, we need an estimate of how strongly a signal has peaked in the recent past. This can be done using slop~ as shown:

Here the abs~ object takes the input’s absolute value (known in electronics as “rectification”) and the slop~ object is set to have no linear region at all, but a rise region with an infinite (1e9) cutoff (so that it follows a rise in the input instantly), and a decay region with a controllable cutoff frequency that sets the speed of the decay. Here is the response to the same rectangular pulse input as the example above:

(In order to keep the same time scale, 100 samples, as above we have here set the decay speed to 1000 Hz, but for an envelope follower this will normally be between 0.1 and 5 Hz. Lower values will result in a less jittery output when an audio signal is input, but higher ones will cause the output to react faster to falling signal levels.) The result is in linear amplitude units, and can be converted to decibels for metering as shown in the help patch.

Audio engineers make frequent use of dynamics processors such as companders (compressors/expanders) and limiters. Companders are most often used to compress the dynamic range of an audio signal to make it less likely that the level falls outside a useful range, but are also sometimes configured to expand dynamic range below a chosen threshold, so that they act as noise gates. Limiters are often used with instruments such as percussion and guitars whose attacks can have much higher amplitude than the body of the note. To hear the body one turns the gain up, but then one has to limit the attack amplitude in order to avoid distortion.

There is no one standard design for a dynamics processor, and few makers of modern ones have divulged their secrets, which might take the form of nonlinear transfer functions, carefully tuned filter parameters, and perhaps many other possible fudge factors. There is also a whole industry in which software designers try to emulate analog hardware dynamics processors. There are also stereo compressors (for mastering CDs and LPs) and multi-band ones. Engineers frequently allow one signal to control the level of a different one, in a technique popularly known as “side chaining”. If one is working from recorded tracks (as opposed to live sound), it’s possible to look ahead in the recorded sound to reduce the distortion that inevitably occurs when a limiter is hit too hard. And so on.

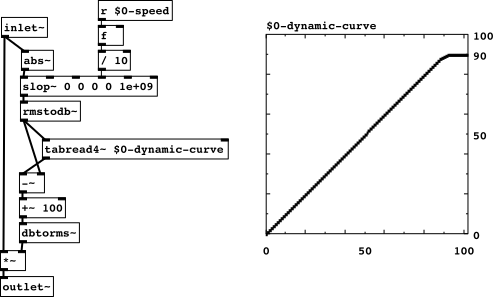

Here we’ll describe a fairly straightforward design based on the instant-attack envelope follower described in the previous example. (This is somewhat atypical; the implications of this approach are discussed a bit later.) Once the envelope is determined (and converted to decibels), a table lookup gives the desired dynamic, and the necessary gain is computed and applied. Thus:

Since the envelope follower has an unlimited rise speed, it will report rises in the signal amplitude without delay. Its output is thus always at least equal to the absolute value of the input. A dynamic curve is then used to compute the desired gain - this gain (in decibels) is equal to the difference between the curve value and the envelope follower output itself. When this gain is applied the resulting signal level is at most what is shown on the curve (equal to it when the signal and the envelope follower agree exactly).

In effect, rising edges of the input signal, when they push outside the currently measured envelope, will be soft-clipped according to the dynamic curve. When the signal drops in amplitude the envelope follower relaxes at a speed decided by the user, and this is heard as a gradual change in gain. (Specifically, a decrease in gain if we are compressing and/or limiting.)

Because the dynamic curve acts as a saturation curve when the signal level is rising, in a situation when we are using it as a limiter (so that the curve is flat at the right-hand end), it is often desirable to make the dynamic curve level off smoothly. In this patch there are three parameters to configure limiting: the limit itself, a boost in DB to apply before limiting, and a “knee” which is the interval, in decibels, over which the dynamic curve bends from the 45-degree angle at low levels to the flat region where we reach the limit.

in addition there is a compander function controlled by two other parameters, “thresh” (a threshold, in decibels, below which companding is to be done) and the percentage, normally between 0 and 200, by which the dynamic range should be altered below that threshold. The “speed” parameter is the speed, in tenths of a Hz., at which the envelope follower output decays.

By setting the linear cutoff frequency to zero and the linear region to an interval of length a (either by setting n = 0, p = 1 or n = p = a/2), and then setting kn = kp = inf , we get a filter that allows its input to jitter over a range of a units before the filter responds to it. This is sometimes useful for quieting down noisy control sources (such as envelope followers or physical sensors). This is analogous to a loose physical linkage.